Why Primary Care Is Dying in the U.S.

- Nate Swanson

- May 14, 2025

- 18 min read

Updated: May 19, 2025

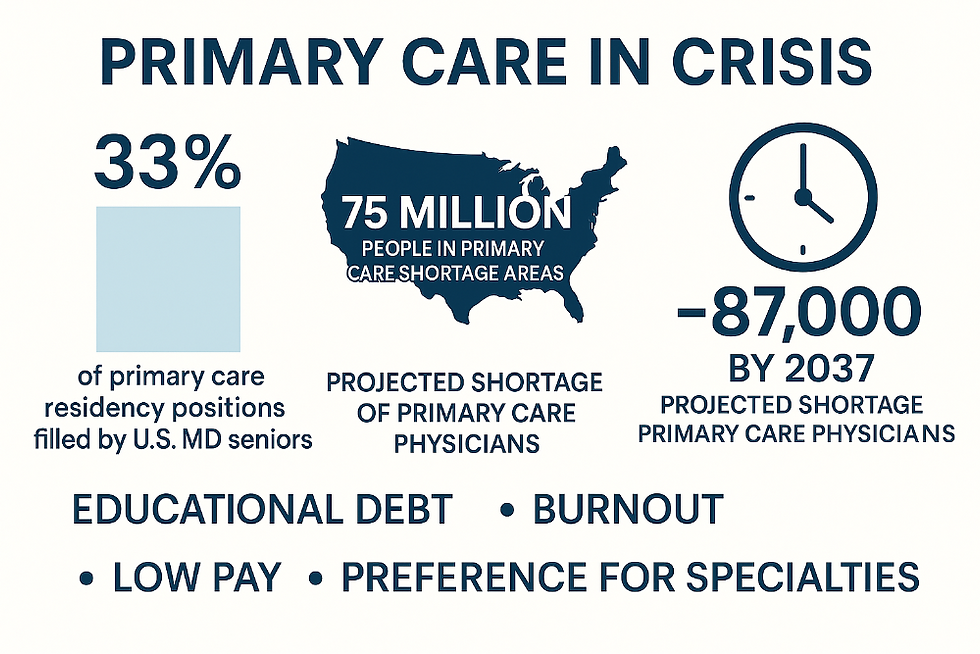

TL;DR: Primary care in America is in crisis. Medical students are increasingly skipping family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics in favor of specialties; as a result, only about one-third of new primary care residency slots are filled by U.S. MD graduates. Meanwhile, roughly 75 million Americans (22% of the population) live in primary care shortage areas, and by 2037 the U.S. is projected to be short ~87,000 primary care physicians. Contributing factors include massive educational debt (despite mixed evidence of its effect), relentless burnout and administrative burden, low relative pay, and a culture that prizes specialties over generalists. Some innovative medical schools and state programs (e.g. NYU’s tuition-free Long Island medical campus) have boosted primary care output, but analysts warn these steps are too little too late. Unless reimbursement, training, and education are retooled, “primary care is dying” may become a reality — threatening population health, raising costs, and widening health disparities.

What Is Primary Care — and Why Is It Dying?

Primary care clinicians (family doctors, general internists, and general pediatricians) are the first line of medicine. As defined by the National Academies, primary care offers “integrated, accessible health care services” and often includes preventive care, chronic disease management, and a continuous partnership with patients and their communities. In practical terms, a patient’s “usual source of care” — the trusted doctor who handles routine checkups, minor illnesses, vaccinations and referrals — is almost always a primary care provider. Research consistently finds that greater primary care access leads to better health outcomes. Populations with more primary doctors have lower overall mortality, especially from heart disease, cancer and respiratory illnesses, and they use more preventive services (like cancer screenings and immunizations). In short, primary care isn’t just another part of the system — it’s the foundation of healthy, efficient health care.

But today that foundation is cracking. The U.S. faces an acute shortage of primary care doctors. One recent analysis warns the country needs 13,000–17,000 additional primary care physicians just to eliminate current federally-designated shortage areas, and by 2037 the gap could swell to roughly 87,150 doctors (about 27% shortfall). The need is especially acute in rural and underserved areas: as of 2024, 7,501 primary-care Health Professional Shortage Areas cover about 75 million Americans (22% of the population). Without enough family doctors, internists and pediatricians, Americans have longer waits, sicker populations, and heavier reliance on hospitals. In fact, health-policy experts warn that access has “crossed a line from which recovery will be difficult,” noting rising maternal mortality, obesity, and other chronic problems as direct consequences of primary care gaps. In short, when primary care withers, the whole health of the nation suffers.

The Vanishing Pipeline: Doctors Opting Out of Primary Care

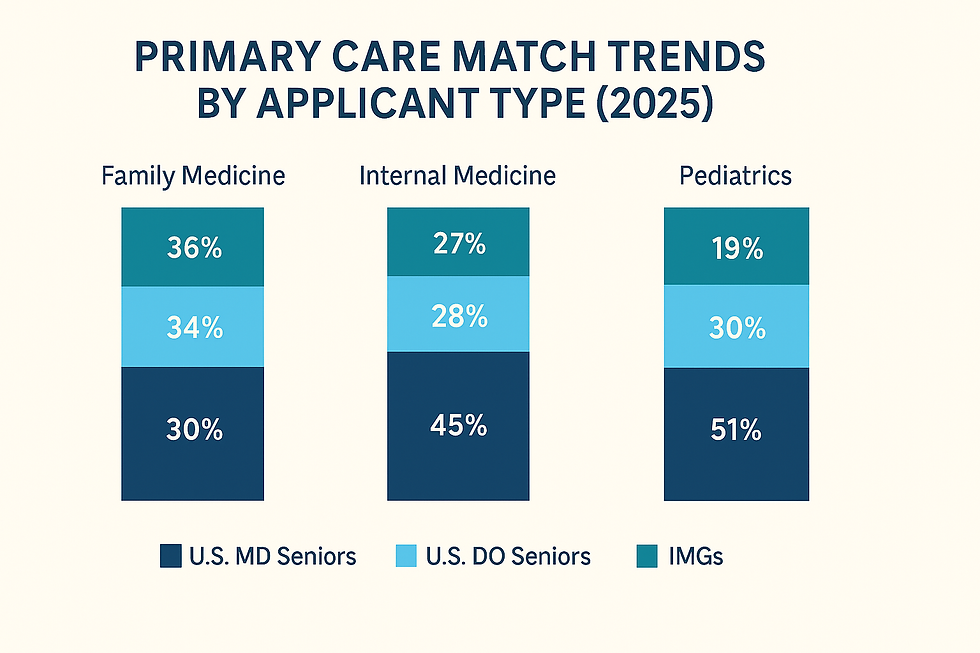

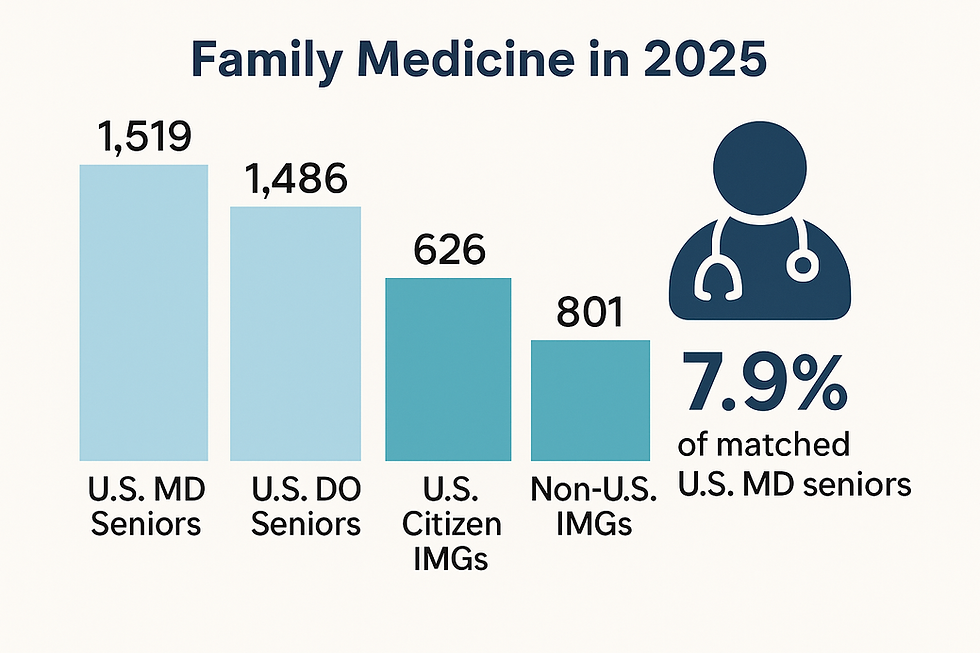

Part of the problem is plain math: fewer U.S. medical graduates are choosing primary care. The residency match data tell the story. In the 2023 Main Residency Match, a record number of primary care residency spots were offered (18,312 categorical positions), but only 38.1% of those slots were filled by U.S. MD seniors. The rest went to U.S. DOs and international medical graduates (IMGs). By 2025 the mismatch is even starker in family medicine: of the 5,379 family medicine slots offered in that year, only 1,519 (≈33%) were filled by U.S. MD seniors. Family medicine in 2025 saw just an 85.0% fill rate, meaning many slots went unfilled or had to be offered through the scramble (SOAP). (By contrast, internal medicine and pediatrics programs typically fill 95–97% of slots, underscoring that family medicine is lagging.)

Even more telling is who is taking the rest of the slots. In 2025 the number of U.S. DO seniors entering family medicine (1,486) nearly equaled the number of U.S. MD seniors (1,519). And international grads account for a rising share: 626 U.S. citizen IMGs and 801 non-U.S. IMGs matched into family medicine in 2025. As one report wryly notes, “nearly a third of all active Match applicants” are now IMGs. Put bluntly: American MDs are shunning primary care in record numbers, forcing DOs and IMGs to fill the gap. Only about 7.9% of matched U.S. MD seniors went into family medicine in 2025 — a historic low compared to the 1990s peak.

This trend shows up across primary care. The National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) tracks family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics collectively. In 2023 there were 18,312 primary care categorical positions (full residency tracks) offered, up 17% from five years earlier, but the applicant pool’s composition shifted. Over the last decade the “ratio of positions per U.S. MD senior” hit an all-time high of 1.90 (meaning nearly two slots for every MD applicant) — implying more slots than graduating doctors. Conversely, DOs had a ratio of 5.03, meaning far more positions relative to each DO applicant. In plain language, there are plenty of residency spots waiting, but fewer U.S. MDs racing to fill them.

The upshot: Primary care is becoming dependent on DO and IMG graduates. That isn’t inherently bad, but it marks a dramatic shift. Historically, U.S. MDs supplied the lion’s share of family doctors. Now, DO schools (with far fewer applicants) and IMGs are shouldering more of the load. If this trend persists, we risk a healthcare workforce dominated by non-MD providers — a sign of how deeply the specialty has fallen out of favor.

Why Are Students Avoiding Primary Care? (The Root Causes)

It’s not the medical schools that are the problem; it’s the job. Behind the headlines about shortages lie real disincentives shaping students’ choices. Below are some of the key factors pushing trainees away from family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics:

Debt (Myth and Reality): Med school debt averages ~$205,000 per student, and many assume that higher debt should steer students into higher-paying specialties. But the evidence is mixed. The AAMC reports year after year that debt has little measurable influence on specialty choice. Students themselves rank “specialty content and personality fit” as top factors, with debt consistently at the bottom. In practice, tuition-free programs (like NYU or Washington Univ.) have not dramatically shifted career picks: at NYU’s subsidized campuses, the outcomes differ (NYU Long Island has many primary care grads vs. Manhattan, but both are debt-free). In short, relieving debt alone is unlikely to revive primary care interest, though it may remove one worry.

Burnout and Workload: This is a biggie. Primary care physicians face crushing workloads and administrative tedium. In a nationwide survey, more than half of U.S. primary care doctors reported feeling burned out, and of those, one-third planned to stop seeing patients within 1–3 years. Burnout in primary care is driven by endless paperwork, high patient loads, and bureaucratic hassles. Primary doctors often spend more time clicking on computers than talking to patients: one study found PCPs spend ~36 minutes on electronic health records for every 30-minute visit, much of it after hours. “Pajama time” — logging into the EHR at night — is routine. These conditions “truly allow people to live longer with a better quality of life,” but only if the system isn’t strangling their spirit. Students hear these horror stories and internalize them. Why sign up for a specialty where the job is often characterized as “toxic” and relentlessly stressful?

Administrative Burdens: As a medical student, it’s hard not to notice how much of primary care seems dominated by non-medical work — and that’s a huge turnoff. From the outside, it looks like primary care physicians spend more time battling insurance requirements and clicking through EHRs than actually treating patients. That’s not why I went to med school. Burnout in primary care isn’t just about workload — it’s about the kind of work. Prior authorizations, billing codes, endless documentation — these tasks are draining and far removed from what draws us to medicine. It feels like primary care has been redefined by admin rather than patient care. In outpatient rotations, students often see this firsthand: attendings juggling complex charts, chasing down referrals, or spending evenings catching up on notes. Unlike specialties where physicians might get protected academic time or even lunch breaks, primary care often feels like a grind from the moment the clinic opens. When that’s our introduction to the field, it’s no wonder many of us walk away.

Income and Financial Incentives: By and large, primary care pays less than most specialties. Although we won’t cite Medscape salaries here, the income gap is real. That gap looms especially large given the time and effort invested in training. In practical terms, an orthopedic surgeon or radiologist can make two or three times what a family doctor does, with comparable hours in the hospital. Even though the U.S. has modest PC-to-specialty pay differences by global standards, the perception of “why not do surgery instead?” is widespread. For medical graduates with sky-high debt (true or perceived), the promise of a big specialist paycheck — or the prestige that comes with it — is often irresistible.

Prestige and Peer Pressure: Medical culture has a hierarchy, and it often puts primary care near the bottom. Anecdotes from schools nationwide describe students and even faculty questioning peers who choose family medicine: “If you’re so smart, why not go do cardiology?” These attitudes reinforce a view that primary care is a fallback. Many medical students across the country report being questioned — even by mentors, peers, or family — about whether choosing primary care means wasting their education. When half your classmates are competing for high-profile specialties, it’s easy to feel secondary. Some researchers argue that without a clear shift in culture — making family docs the heroes of population health — attitudes in med schools won’t change.

Training Environment: As one analysis observes, medical students rotating through outpatient clinics often see under-resourced practices and stressed doctors. In contrast, hospital rotations tend to feel glamorous and well-supported (and students routinely notice hospital teams being fed lunch, for instance). These early impressions stick. If your primary care mentor is frazzled and underpaid, it subconsciously drives you to other paths. Studies also show that students who do a lot of primary care clerkships or have strong mentors are more likely to choose it, but many schools lack robust programs for that. In short, the way we train future doctors often fails to sell the joys of family medicine.

These factors compound each other. The result is unsurprising: U.S. MD graduates tend to chase specialties. One report summarized the outlook plainly: “There’s really very little that we can do in medical school to change people’s career decisions”, said a family medicine advocate — implying the problem is with healthcare itself. In other words, unless the conditions of primary care become more attractive, simply preaching its value in orientation won’t stem the tide.

Building the Pipeline: Innovative Fixes and Their Limits

Given the shortages, some schools and programs have launched creative “pipeline” efforts to steer more doctors into primary care. These range from scholarships to mission-driven admissions to whole new institutions. A few examples stand out:

Tuition-Free Medical Schools: In recent years several leading schools have eliminated tuition entirely, hoping that debt-free graduates will follow their passions. Washington University (St. Louis), Columbia, UCLA, and all of NYU are now tuition-free or nearly so. The largest experiment is NYU School of Medicine’s two campuses: the flagship Manhattan campus (NYU Grossman) and the newer Long Island campus (NYU LISOM). Both offer free tuition, but with different missions. At the new NYU Grossman Long Island School of Medicine, founded in 2019 specifically to tackle primary care shortages, the results are striking: two-thirds of its 2024 graduates entered residencies in primary care specialties. In contrast, the urban NYU campus (in Manhattan) — despite also being tuition-free — saw most of its 2024 grads choose high-paying fields like orthopedics and dermatology. The lesson: debt relief alone didn’t push everyone into family med, but combining free tuition with an explicit “community primary care” mission (as NYU LISOM has) seems to work.

Targeted Admissions and Scholarships: Beyond whole-school models, some programs explicitly recruit students likely to become primary care doctors. Many medical schools reserve slots or programs for applicants with rural backgrounds, or who express interest in caring for underserved populations. For example, some state-supported schools now require a percentage of students to train in rural sites or work in “community health centers.” Donors have funded scholarships tied to service in family medicine. One study noted that graduates of such pipeline programs (e.g. at University of Kansas or Penn State’s Milton S. Hershey School) are disproportionately matching in primary care, far above their peers. Even the Milbank Scorecard recognizes that “creative financing and admission processes” — like free tuition and diversity efforts — are being tried to steer more students into generalist fields. A law school in Texas, for instance, developed a program that admits more graduates from disadvantaged backgrounds, and found those alumni were much more likely to practice in underserved communities (see sidebar).

State-Funded Initiatives: Several states have taken bold action on their own. California’s “Future Health Workforce Commission” back in 2019 recommended expanding family medicine residencies, loan repayment, and other tactics to meet a projected shortfall of 4,100 PCPs by 2030. Since then California has launched new family medicine residency slots, raised loan forgiveness amounts, waived tuition for some, and even set a statewide target to bump primary care spending as a share of total healthcare (inspired by models in Oregon and other states). It has poured hundreds of millions of dollars into these efforts. “The pieces are there,”says Covered California’s CMO, “but we started too late and it’s too siloed.”. Other states have similar programs: Oregon set aside billions to increase primary care physician supply and capitate pay, Hawaii reduced medical school tuition for family med tracks, and numerous rural areas have “rural track” residencies with guaranteed jobs in those communities. Some health systems (e.g. Kaiser Permanente) operate their own residency programs in underserved regions.

Each of these examples shows promise, but also limits. Many of the new initiatives began in the last few years — too recent to fully move the needle. And as California’s experience suggests, efforts can be fragmented across agencies and school, lacking the coordination to produce a sea change. Still, these innovations do demonstrate what could work: remove financial barriers, train students in community settings, and align incentives from day one.

What Happens to Patients When Primary Care Declines?

When local primary care disappears, the impact on patients and public health is profound:

Worse Health Outcomes: Counties with fewer primary doctors see higher death rates from preventable causes. A landmark study in JAMA Internal Medicine found that greater primary care physician density was linked to significantly lower mortality from cardiovascular disease, cancer and respiratory illness. In practical terms, each additional family doctor per 10,000 people translated to hundreds fewer deaths per 100,000. Conversely, the American Family Physician chartbook warns that the U.S. is not investing nearly enough in primary care infrastructure, which already contributes to rising chronic diseases and declining life expectancy. Milbank reports confirm that as the supply-demand gap widens, overall population health is worsening: life expectancy has stopped improving, and issues like obesity and behavioral health disorders are surging. Without enough PCPs to manage diabetes, blood pressure and other conditions early on, people suffer preventable complications.

Greater Disparities: The shortages aren’t evenly distributed. Rural areas and low-income urban neighborhoods have the thinnest coverage. In fact, 66.5% of primary care shortage-designated areas are rural. For example, KFF reports that nearly 15 million Californians (a highly urbanized state) live in areas without enough PCPs. Nationally, the percentage of people who report no usual source of care — no family doctor to call — has been rising for all groups. From 2012 to 2021, the share of adults lacking a usual doctor jumped 21%, and for children by 36%. These trends hit minority and low-income populations hardest, exacerbating health inequities. People without a steady doctor are more likely to skip preventive care (like vaccinations and cancer screenings) and to delay seeking treatment. The CDC notes that uninsured or underinsured patients end up hospitalized more often for conditions that could have been managed in primary care. In short, weak primary care furthers health disparities and fuels a vicious cycle of illness.

More Costly Care: When there’s no doctor to call, patients use the emergency department or urgent care more often. Research shows that having a regular PCP reduces unnecessary ER visits and hospital stays. By contrast, areas with primary care shortages see higher avoidable admissions (e.g. for asthma or diabetes) and higher costs. Patients also lose coordination of care: a family doctor catches problems early and manages multiple conditions, which specialists alone often cannot. Anecdotally, physicians say that without PCPs, patients end up “ping-ponging” among specialists and uncoordinated services — not only frustrating families, but driving up spending.

Fragmented Care Models: Some of the response to the PCP gap has been growth of retail clinics, telehealth services, and “hospitalist”-style urgent care teams. These can treat immediate symptoms but don’t replace an ongoing relationship. The Milbank report warns that U.S. primary care is splitting into two arms: one offering traditional continuous care (if you can find it), and another of episodic clinics and telemedicine visits. Continuity and prevention suffer. In effect, primary care’s role as gatekeeper and health manager is diluted, causing worse long-term health trends.

In summary, the decline of primary care access is not just a staffing issue – it’s a population health emergency. Patients without physicians catch illnesses later, have more unmanaged chronic disease, and experience more preventable harm. Meanwhile public health goals (like the Healthy People 2030 objective to increase the proportion of people with a usual PCP) become ever harder to reach.

Are Current Policies Helping?

Faced with this alarm, policymakers and organizations have launched many initiatives. How effective are they?

Federal Actions: Congress and federal agencies have taken steps. In 2021, Congress passed the Consolidated Appropriations Act which – for the first time in 25 years – authorized 1,000 new Medicare-supported residency positions. These slots will be phased in over several years (up to FY2027), and by 2033 are expected to produce about 1,600 additional doctors. The legislation gives priority to hospitals in underserved areas, new medical schools, and rural programs, aiming in part to boost primary care. (There are even proposals in Congress to further raise the cap by 14,000 positions, focused on community hospitals and rural tracks, but those bills have not yet passed.)

The federal government also bolsters primary care via loan repayment and service programs. The National Health Service Corps (NHSC) alone supports over 17,000 primary care providers in shortage areas through scholarships and loan repayments. NHSC clinicians serve at thousands of clinics nationwide, improving access in remote and poor communities. HRSA has increased loan forgiveness amounts for primary care commitments and expanded Title VII/Title VIII educational grants to train more generalist physicians and nurse practitioners. The White House and NIH have occasionally spotlighted primary care in policy reports or funded research on family medicine practice. Furthermore, some Medicare payment reforms attempt to reward primary care (e.g. Medicare’s Primary Care First initiative).

However, many analysts say federal efforts are fragmented or underwhelming. A key issue is how GME dollars flow. Milbank’s 2025 report points out that most Medicare GME funds still go to large hospitals and specialty programs, not community-based or rural residencies. In fact, one analysis found that states with more Medicare GME funding actually produce a lower percentage of PCPs among their new physicians. In other words, money is piling up where specialists train, while comparatively little supports primary care residencies. HRSA’s 2024 workforce report echoes this: only a tiny fraction (about 5.1% of primary care residents) train primarily in outpatient clinics serving underserved patients. Experts argue this mismatch undermines federal GME expansions: if new slots are mostly at big teaching hospitals, they won’t necessarily turn into more family doctors in towns where they’re needed.

State and Local Initiatives: Many states have tried more targeted tactics. California, for instance, has become something of a lab. Inspired by a state commission’s 2019 goals, California instituted a slew of measures: it created hundreds of new residency positions in family medicine and primary care; offered bigger loan repayment and scholarships for choosing PCP; expanded nurse practitioner scope of practice; and even set an ambitious goal to raise primary care spending (from the typical ~5% of total Medicaid spending) to around 10%. It also funded pilot programs paying doctors bonuses for hitting prevention targets. KFF reports that despite these moves – and hundreds of millions invested – experts still call the effort “scattershot.” California did climb 10 places (out of 51 jurisdictions) in primary-care physicians per capita rankings between 2020 and 2023, but by 2025 15 million Californians remained in primary-care deserts. Budget constraints and potential federal cuts (e.g. to Medicaid) also loom as threats to this progress.

Other states have had mixed success. Oregon pioneered a major reform by increasing Medicaid rates for PCPs to be competitive with Medicare, and creating a large reserve for primary care clinics; it also set ambitious workforce targets. Massachusetts, New York and others have funded academic centers for primary care research and training. Yet even with these efforts, wait times remain long. A recent Milbank analysis notes that in many areas wait times to see a PCP can be nearly a month. Outpatient clinics are still understaffed, and primary care spending in the U.S. hovers around 5–6% of total health dollars – far below countries like the UK or Canada. On the whole, policy fixes have helped marginally, but they have not turned the tide of declining interest.

What Would It Take to Reverse the Trend?

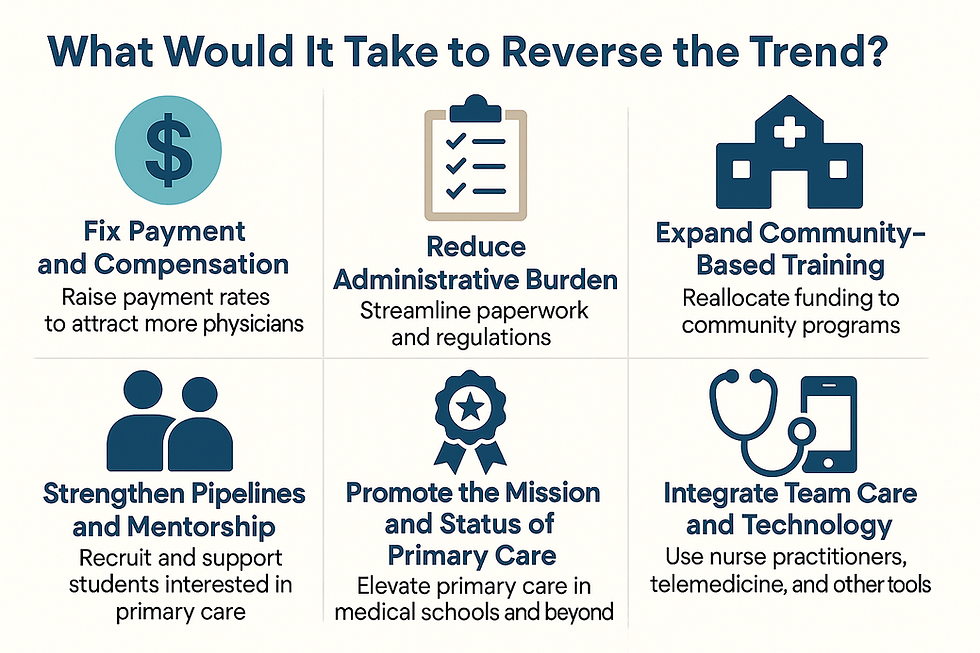

Reversing the decline of primary care will likely require a multi-pronged assault on its root causes. Experts have several prescriptions:

Fix Payment and Compensation: Primary care pays less per service than most specialties. Making it more financially attractive is critical. Many recommend raising Medicare and private payment rates for evaluation-and-management (E&M) visits to narrow the gap. Models like advanced primary care payments or global budgeting (used in some states) help stabilize PCP practices. CMMI’s success in giving upfront payments for care management, and proposals to reform Medicare’s Physician Fee Schedule to favor cognitive care, are steps in this direction. If being a family doctor paid as much as being a specialist for equal work, more students would consider it.

Reduce Administrative Burden: Streamlining paperwork, improving EHR usability, and cutting unnecessary regulations would make day-to-day life much better for primary care teams. For example, simple fixes like minimizing prior authorization for evidence-based medications can save doctors hours every week. In health systems that have tackled EHR overload (with scribes or better software), physician satisfaction climbs. The AMA’s Joy in Medicine initiatives and AHRQ’s recommendations echo this need to rebuild clinic workflows. If clinics felt like supportive workplaces rather than paperwork gauntlets, more doctors might stay.

Expand Community-Based Training: How we train doctors matters. Studies show that physicians tend to practice where they train. Yet only ~5% of family medicine residents are spending most of their training in community outpatient settings. Reallocating GME funding toward community-based programs — like rural tracks, community health center residencies, or longitudinal integrated clerkships — could seed more doctors into underserved areas. For instance, teaching residencies based at community health centers or veterans’ clinics could produce doctors committed to primary care in those settings. The Milbank report explicitly calls for Congress and CMS to redeploy Title VII/VIII and GME dollars into community-based training environments.

Strengthen Pipelines and Mentorship: Encouraging students early is key. Pipeline initiatives could start as early as college – e.g. partnerships with minority-serving institutions, pipeline programs that bring underrepresented students into medical sciences, or scholarships at the pre-med level for future community physicians. Within medical school, curricula can emphasize community health and include mandatory family med rotations with inspiring mentors. Medical schools could give preference to applicants from rural or underserved backgrounds (who are statistically more likely to become PCPs), as some now do. Schools like OHSU or Appalachian states that emphasize local care see higher primary care yields. Likewise, residency programs can provide loan forgiveness in exchange for service in shortage areas. In short, to reverse the tide we may need to stack the deck in favor of primary care from Day One.

Promote the Mission and Status of Primary Care: Some change may have to be cultural. Elevating the role of primary care in medical education, research, and leadership could improve its image. Campaigns that highlight primary care’s impact (such as studies linking PCP density to lower mortality) can counter the prestige bias. National organizations (like AAFP, AAMC, AMA) and Congress could declare primary care a national priority — perhaps setting explicit PCP-to-population targets. Indeed, countries like Canada and Australia set higher benchmarks for primary care supply. Public recognition (awards, media stories, high-level policy attention) could help reframe primary care as a valued career path.

Integrate Team Care and Technology: The future of primary care may also look very different. Using nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and team-based models can ease the doctor shortage. For example, allowing NPs to practice independently (as some states do) expands the workforce. Leveraging telemedicine can stretch PCP reach into remote areas. On the technology front, if EHRs were smarter and interoperability improved, patient data could be shared seamlessly and doctors could spend more time on care, not clicking. Artificial intelligence or virtual health assistants might someday screen patients, flagging only those who really need a doctor’s attention. While these are not quick fixes, investing in practice redesign — from patient scheduling to chronic disease registries — could make primary care more efficient and satisfying.

Ultimately, reversing the decline will require leadership and investment. The recent record Match sizes show there is demand for more doctors overall, but the specialty mix must be guided. The AAMC has advocated for increasing federal funding for primary care training (Title VII grants, teaching health centers, etc.). Many physicians argue for Medicare to pay much more for cognitive services. Beyond money, it will take a societal choice to prioritize prevention and wellness over the lucrative procedure-driven model. If higher-ups in medicine and government double down on strengthening primary care — through laws, incentives, and public campaigns — we might slow or halt the attrition.

Conclusion: The Stakes Are High

Primary care is the keystone of a healthy society. When it erodes, everybody pays a price: patients get sicker, poorer communities fall further behind, and the healthcare system becomes less efficient. Right now, the warning signs are all there. We have fewer U.S. medical students entering the field, a graying physician workforce (one-third of doctors over age 65 in a decade), and rising burnout that threatens to drive still more out of practice. Life expectancy has dipped, and preventable illnesses are rising — all symptoms of a weakened primary care foundation.

If “primary care is dying”, it’s because the system has for decades undervalued first-contact medicine. The broader implications are profound: without course correction, America’s health outcomes could worsen and costs will climb. The good news is that the crisis is now widely recognized, and some promising solutions are in play. But change requires vision and courage. Will the nation invest in the long-term health of its people by nurturing primary care? Or will we continue to treat it as an afterthought, only raising alarms when the next pandemic or an aging population crashes into a fragile system? In journalism terms, the story is clear — primary care is at death’s door. The question is whether we choose to help it live again.

Like this article? Check out these related articles next!

Comments